< Back to news

Technology is made by people and thus also has the characteristics of the society and culture from which it emerges. This means we must always be wary of which interests technology serves. Who gives direction to it? What does it include or exclude? And perhaps more importantly, who owns it? We cannot talk about technology without also talking about power. In that light, it is strange that the power aspect is not looked at much more critically from an innovation policy perspective. We finance from public funds but have no public control. Instead of providing innovation subsidies to private parties serving shareholder interests, we should keep the outcomes of public investments public. The unbridled belief in market forces is on its way out. It seems that the time has come to shape the public digital domain. It also indicates that technology can never be separated from the social juncture. There are always interests at stake. We must ensure that the development of technology is accompanied by critical reflection and explicit design choices. A process in which social and cultural experts are part of.

September 13, 2023

AI and Big Tech: The potential of the countermovement

What will define the future of arts and culture? Chances are it will be technology. There is no conceivable interaction in which technology does not play a role. In our work, in our health, in exploring the world around us and in our social lives. Our culture is steeped in technology. That is a given. It is not inherently proper or wrong. It means we have a responsibility to guide technology and shape public values in the digital domain.

The word technology comes from the Greek term 'techne' meaning art or fabrication. We can therefore think of technologies as artefacts, they are 'artificially made'. So technology is not something that happens to us, or is present in nature, it does not grow from the ground, nor is it handed to us by a higher divine power. We humans are responsible for it. Donna Haraway puts it in Simians, cyborgs, and women: the reinvention of nature (1991):

'Technology is not neutral. We're part of what we make and it is part of us. We live in a world of connections - and it matters which ones get made and unmade.'

Technology is made by people and thus also has the characteristics of the society and culture from which it emerges. This means we must always be wary of which interests technology serves. Who gives direction to it? What does it include or exclude? And perhaps more importantly, who owns it? We cannot talk about technology without also talking about power. In that light, it is strange that the power aspect is not looked at much more critically from an innovation policy perspective. We finance from public funds but have no public control. Instead of providing innovation subsidies to private parties serving shareholder interests, we should keep the outcomes of public investments public. The unbridled belief in market forces is on its way out. It seems that the time has come to shape the public digital domain. It also indicates that technology can never be separated from the social juncture. There are always interests at stake. We must ensure that the development of technology is accompanied by critical reflection and explicit design choices. A process in which social and cultural experts are part of.

Traditionally, artists have been curious about technology. Not only as 'early adaptors' in applying new technologies, but also as critical observers who question the underlying assumptions. Moreover, artists are also involved in the research and development of technology. Artificial Intelligence, neurotechnology, biotechnology, in each field artists are active and contribute to meaning, design and debate. So the cultural sector is not just a user or consumer of technology, but it also helps shape it.

The new tools

With the latest generation of digital tools, something special is happening. The artwork itself has been turned into a tool. Tech companies have built up data collections with which AI programmes are trained. Music, images, video and text are the raw materials with which new work can be generated.

If you understand the art of 'prompting'1, you can use so-called generative AI programmes like ChatGPT, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney to generate every conceivable essay, article, piece of music, image and video. By playing with the prompt, you can add variations. Give it a tone: upbeat, mysterious or just accessible. A genre: romantic, surreal, or with techno elements. Or give the name of an artist whose handwriting you would like to see reflected in the new creation. In the style of Mondrian, Becket or The Beatles. The better your prompt, the more beautiful the outcome.

Prompt for ChatGPT: 'Write a theatre script in the style of Annie M.G. Smidt in which a young son researches the murder of his father and finds out that the culprit is his uncle whom his mother has just remarried. Use the elements of betrayal, love and revenge and the message that every crime will be punished. Have it set around the Danish court in the year 2040.'

Prompting has quickly become a new skill, including manuals and courses. It would not be out of place in the curriculum of design and art schools. With the usual grandiloquence, this development is described by tech companies as the definitive democratisation of art production. Indeed, it allows untrained people to generate creations of reasonable quality. And professionals manage to use it to generate award-winning works that embarrass juries. For instance, Boris Eldagsen, the winner of the Sony World Photography Award 2023, revealed that an AI programme had generated the black-and-white photograph Pseudomnesia - the Electrician and not him. Incidents like this fuel the debate on what place these new art expressions should have.

The unlimited possibilities also lead to production of a huge amount of clutter. You can have any idea generated in any style. The Wonder AI app advertises prompts like 'George Washington eating a hamburger' and 'Pink elephant playing monopoly'. Follow the hashtag #AIart on Instagram and disproportionate, busty women, mostly in manga style, tumble over you. The more serious creations are a potpourri of what our world culture once produced, in ever-changing variations and guises. A festival of clichés. It also provides every opportunity for deepfakes and mimicking musicians and actors. Recently, Drake & The Weeknd's new song Heart on my sleeve received 8 million views within a short time, but turned out to be an AI fake that was quickly removed. ChatGPT and similar programmes generate lyrics based on a combination of different sources and algorithms. As a result, they tend to fabulate. Full of conviction, the programmes present things as facts where self-generated events and sources are concerned. A welcome quality for art production, but for truth-telling, it is a tragedy. Owners of the generative AIs are now being taken to court for disinformation and its consequences.

It remains to be seen whether the advent of generative AIs will democratise art production. The first payment walls and licensing models have already been spotted. The free versions of ChatGPT are limited, outdated and less accurate. If you take a subscription of 20 euros a month, you have access to the latest version. So you have to dip into your pocket to work with the programmes. We also know this payment model from other so-called authoring tools like Photoshop, Adobe or Avid.

Read the rest of the Boekman article "AI and Big Tech", written by Marleen Stikker, on the Boekman website.

Vergelijkbaar >

Similar news items

September 9

Multilingual organizations risk inconsistent AI responses

AI systems do not always give the same answers across languages. Research from CWI and partners shows that Dutch multinationals may unknowingly face risks, from HR to customer service and strategic decision-making.

read more >

September 9

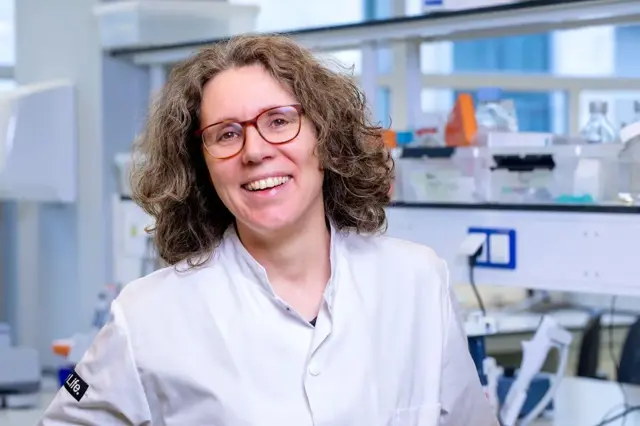

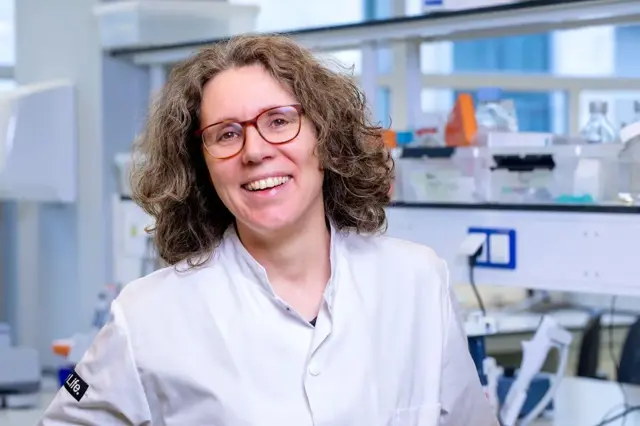

Making immunotherapy more effective with AI

Researchers at Sanquin have used an AI-based method to decode how immune cells regulate protein production. This breakthrough could strengthen immunotherapy and improve cancer treatments.

read more >

September 9

ERC Starting Grant for research on AI’s impact on labor markets and the welfare state

Political scientist Juliana Chueri (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) has received an ERC Starting Grant for her research into the political consequences of AI for labor markets and the welfare state.

read more >